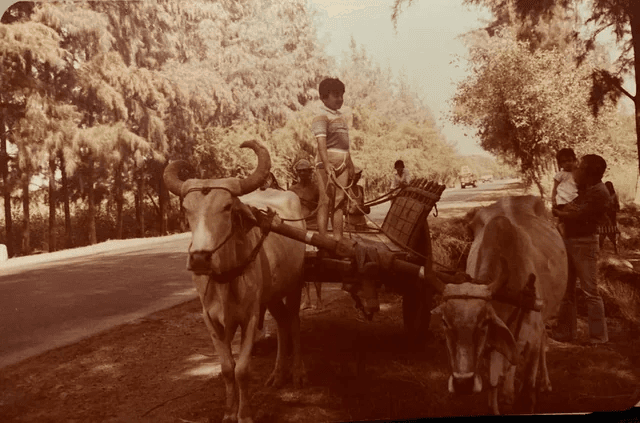

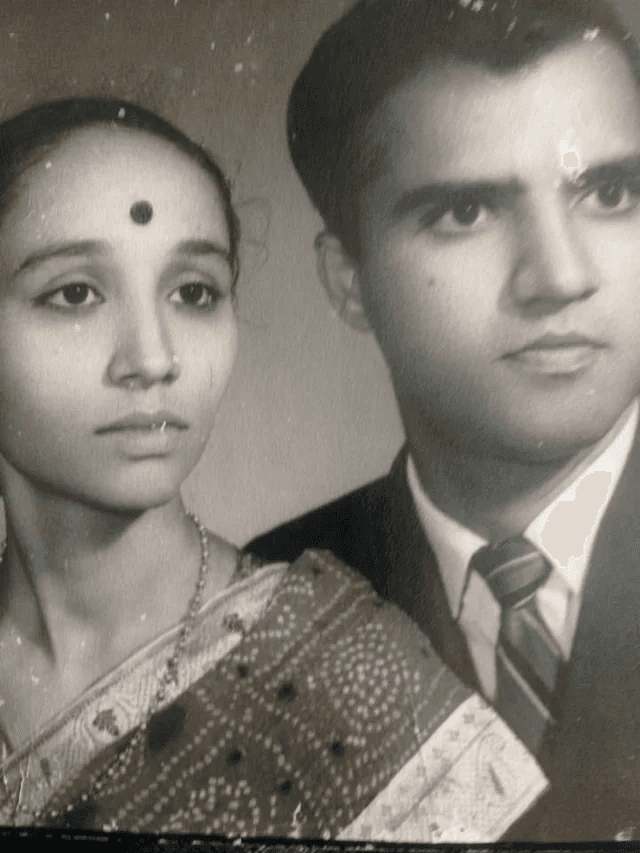

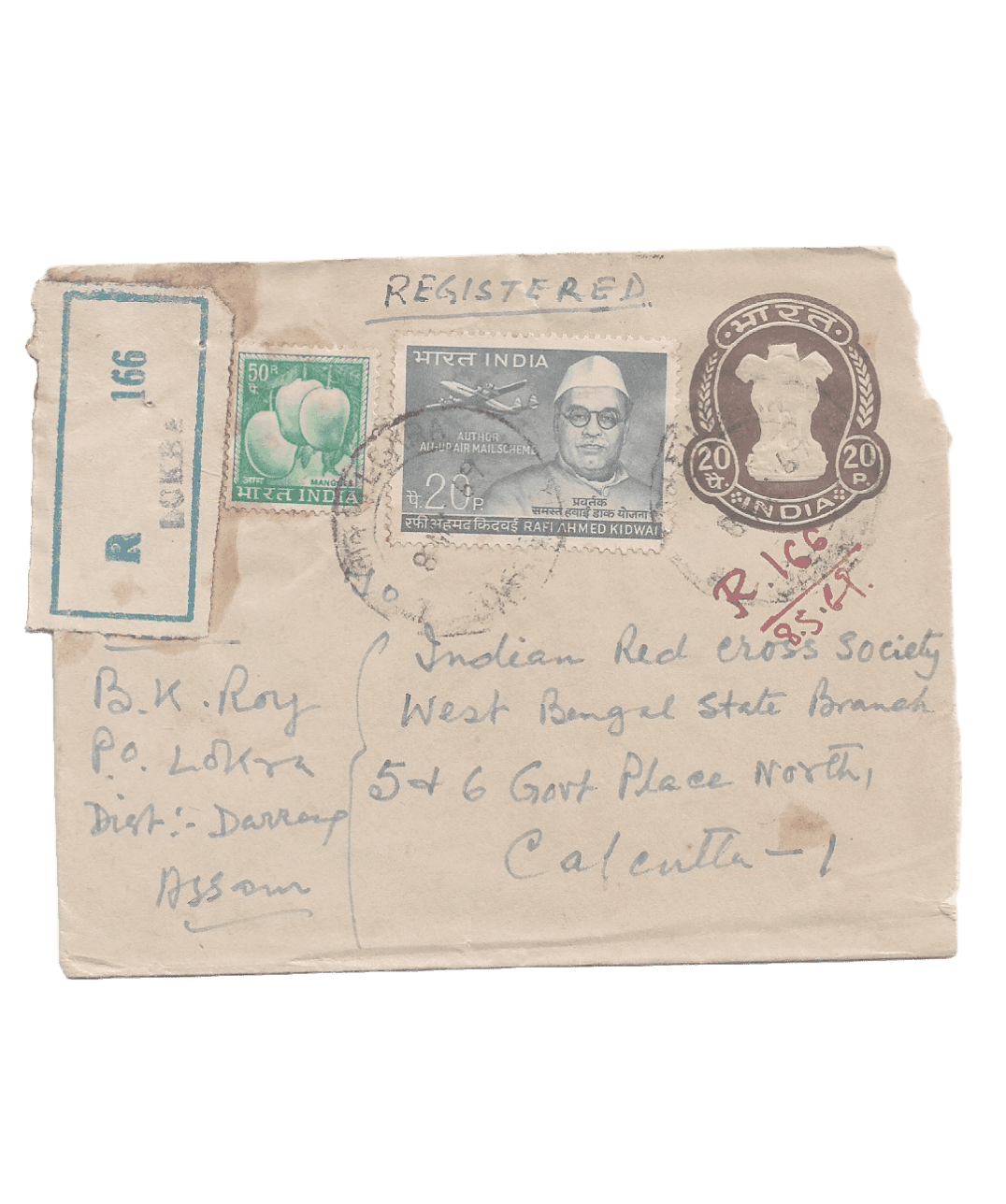

In those days, love travelled by post—and in our house, even the postman felt like a relative.

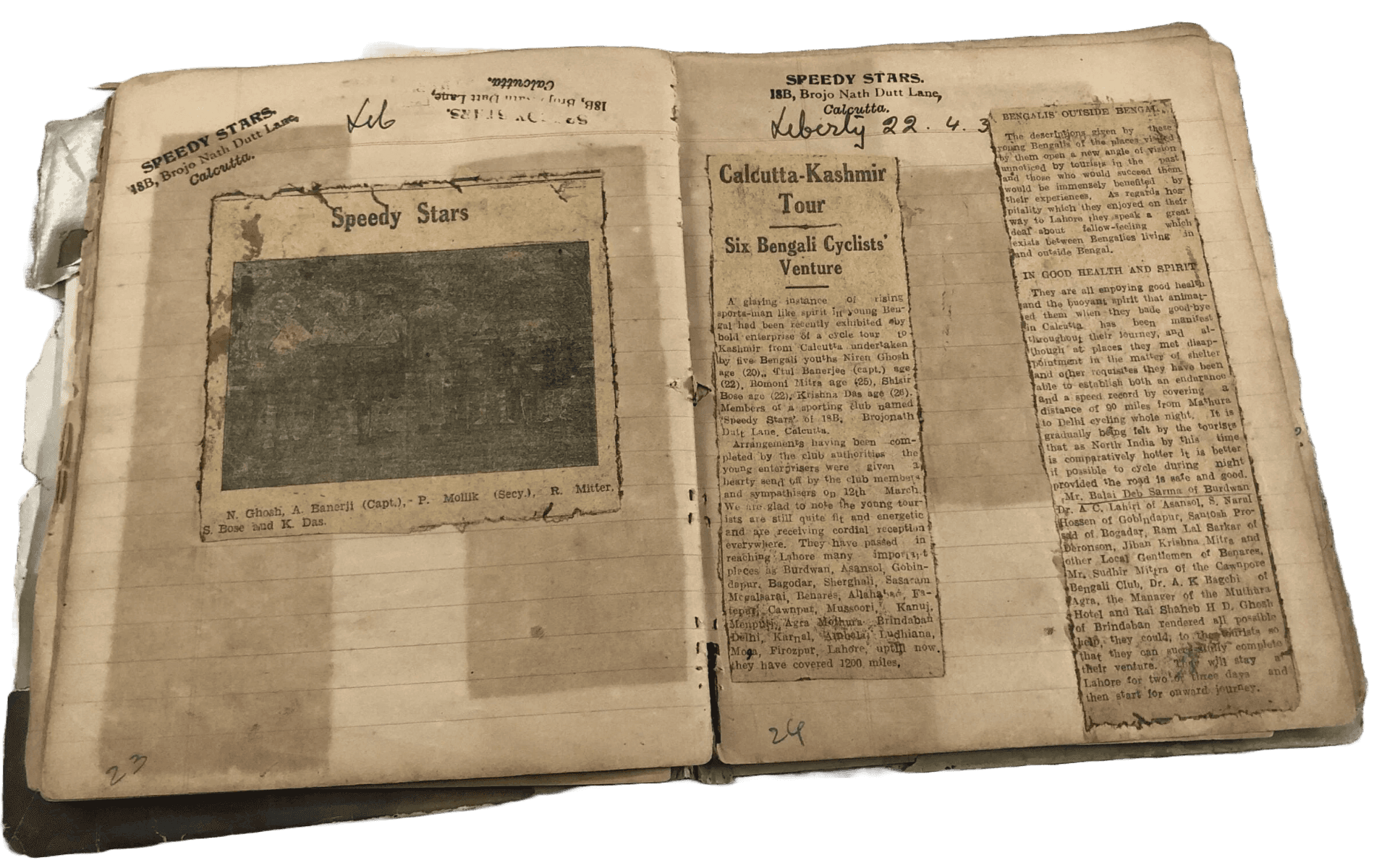

I’d leave work and stop at the little post office, still smelling faintly of sweat and Lifebuoy soap, clutching that thin aerogramme sheet like it was something precious. The clerk would lick the stamp, straighten it with too much seriousness, and then— thap — press REGISTERED on the envelope. That sound used to make my heart steady. As if the government itself was saying, “Yes, this love is going.”

I never wrote filmi lines. I wrote like a normal man: that the power cut came again, that the chai was too sweet at the canteen, that the ceiling fan was making that tak-tak sound, and that the entire day somehow felt incomplete without her voice in it. And then, between those ordinary sentences, I would hide the real thing—one small line meant only for her, the kind that could survive distance and nosy eyes.

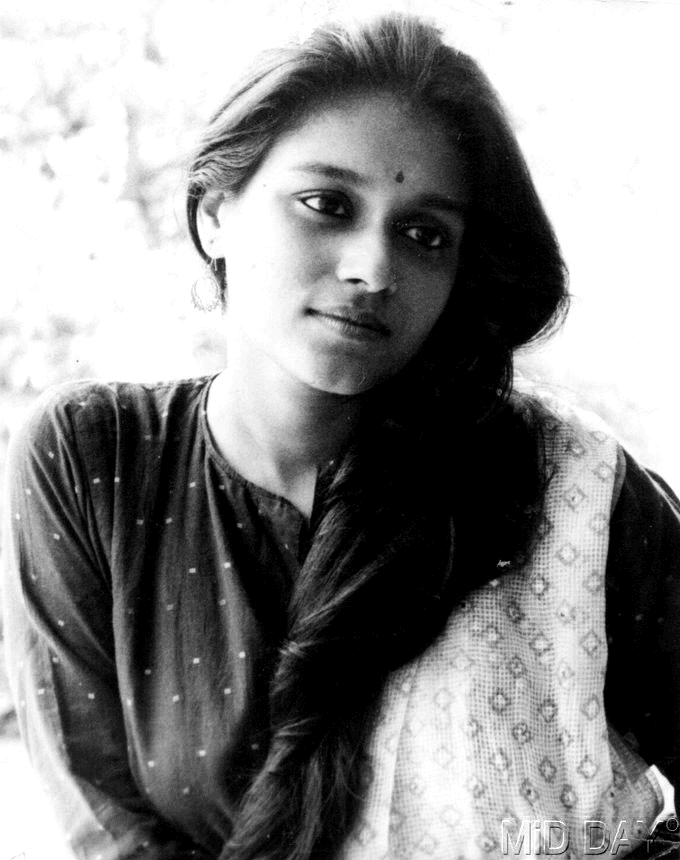

Her replies came after a week, sometimes ten days. The paper would be soft at the folds, like it had been opened and closed a hundred times. She’d write about Amma asking too many questions, about the neighbour aunty who noticed everything, about pressing her dupatta between the pages of a book so the letter could stay hidden. But even in all that, she’d end with something that made me smile like an idiot: “Send another soon,” or “I’m keeping your envelopes in my drawer.”

Now when I look at those stamps, the old printing, the ink that has faded - I don’t just see mail.

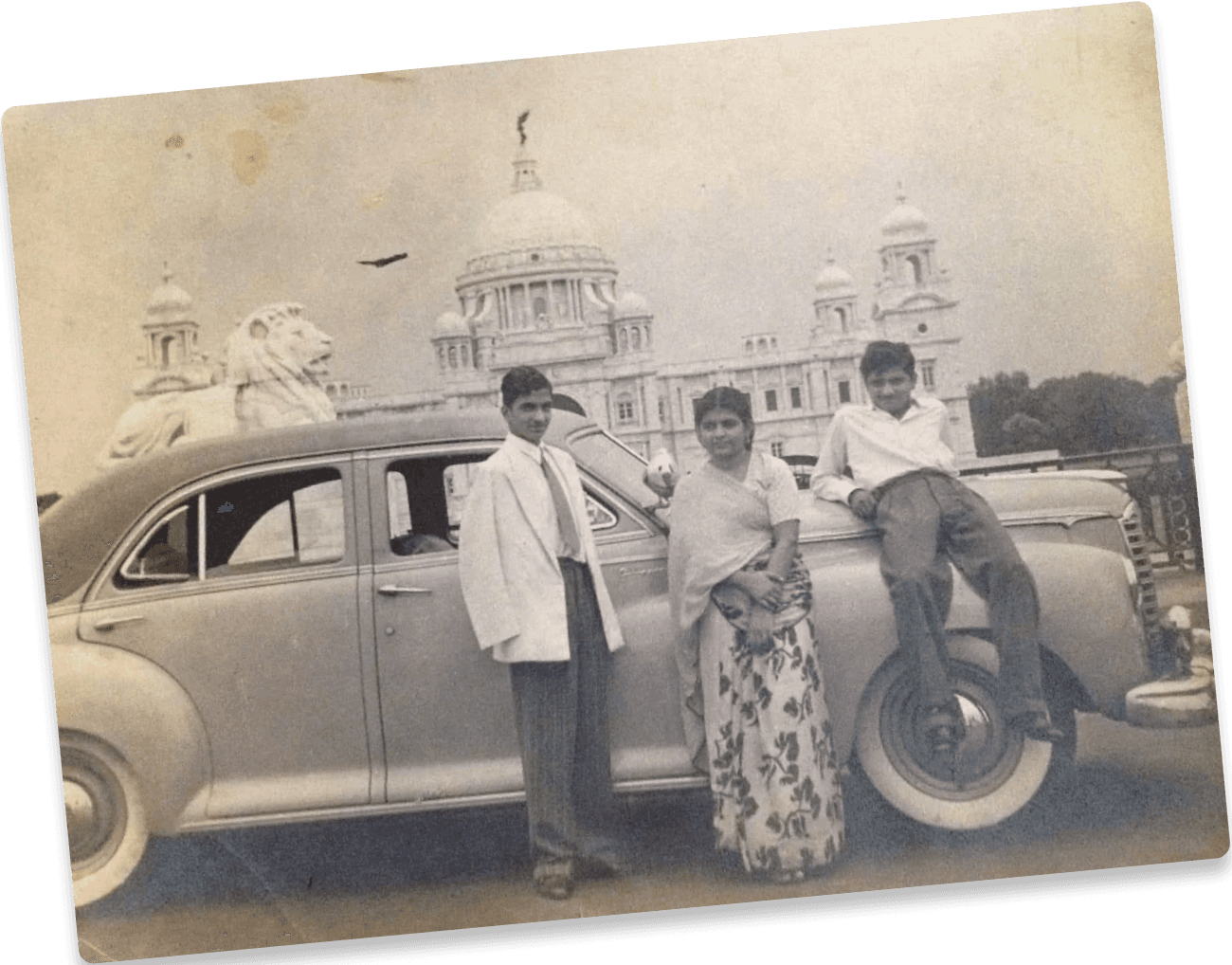

I see the patience we had. The way we loved without hurry. The way we built a life, one letter at a time, between chai, power cuts, and the long wait for footsteps at the gate.

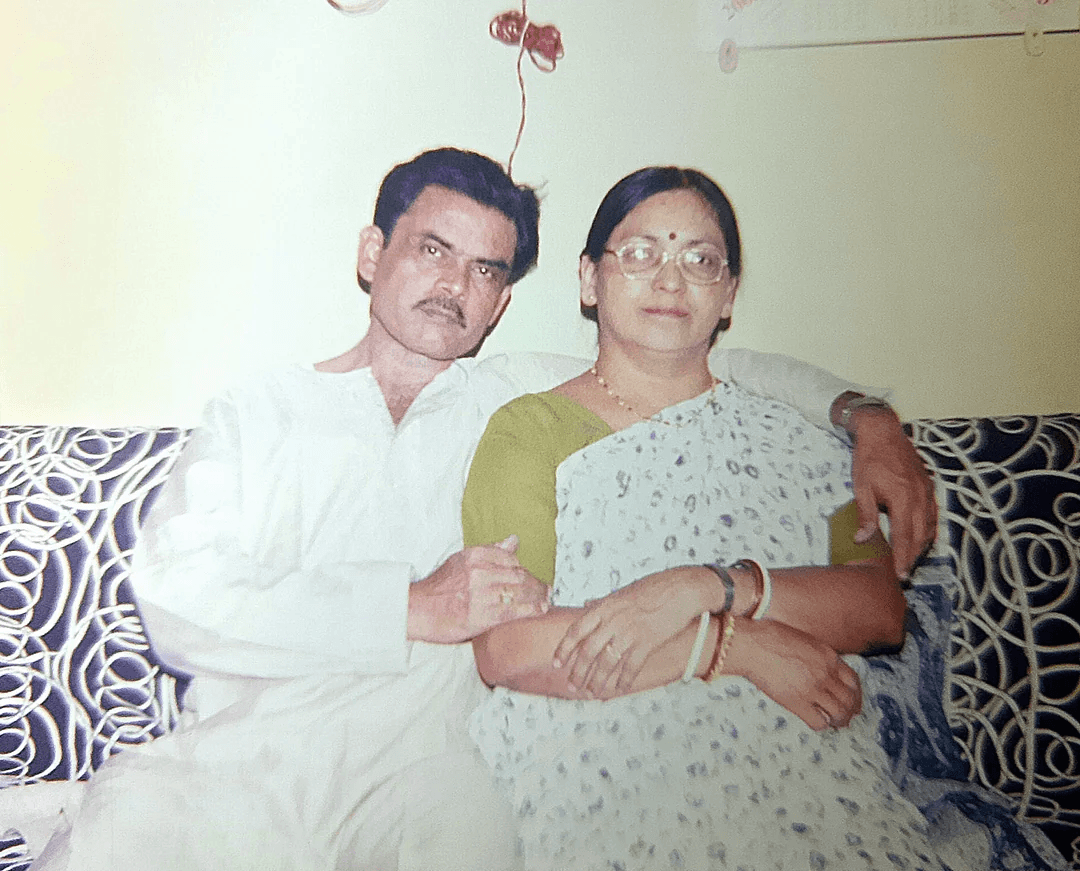

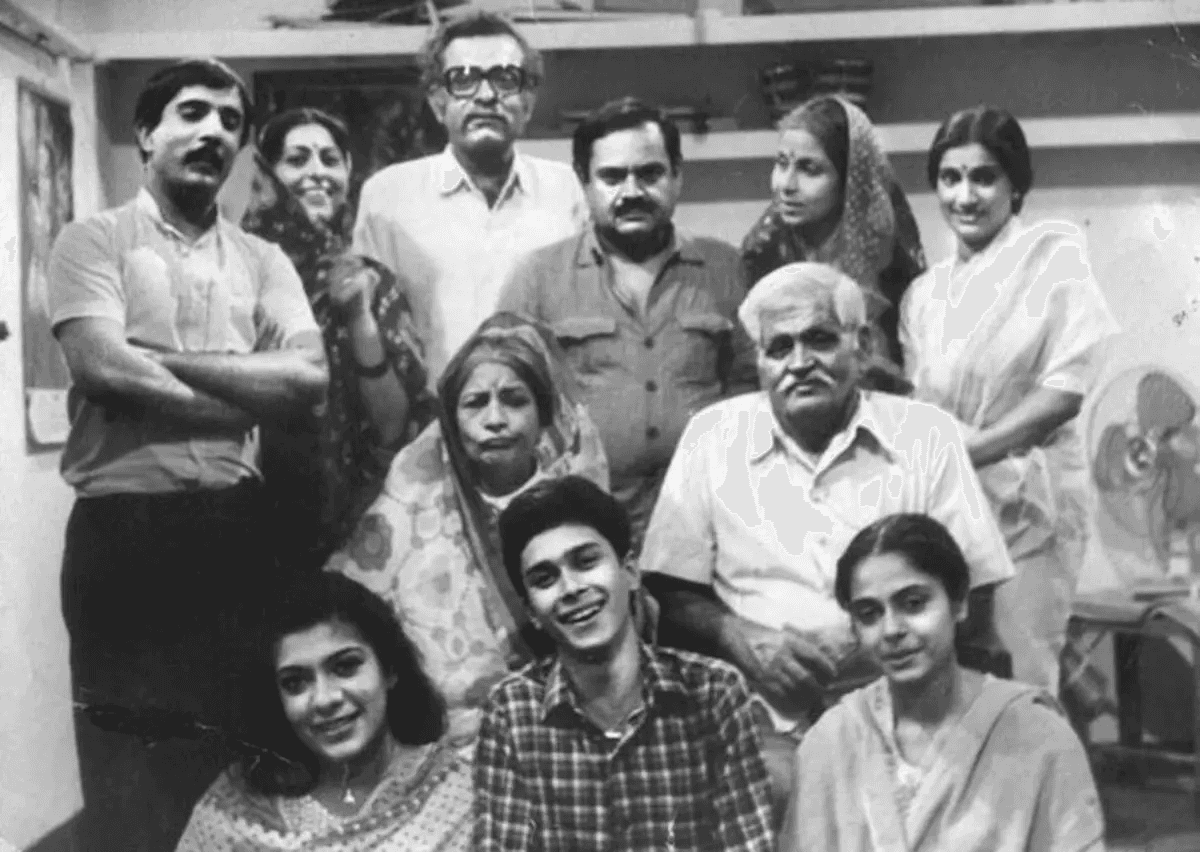

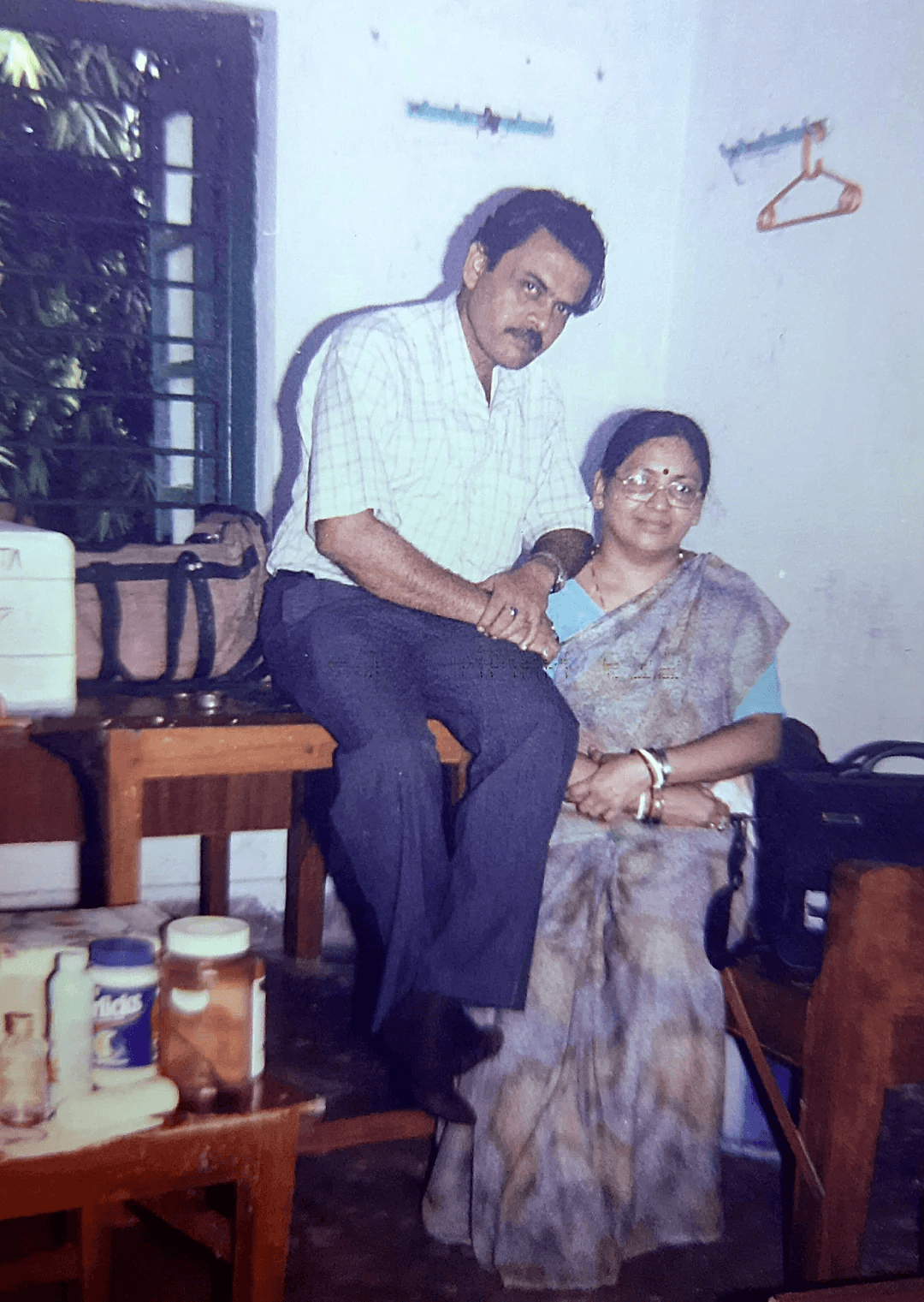

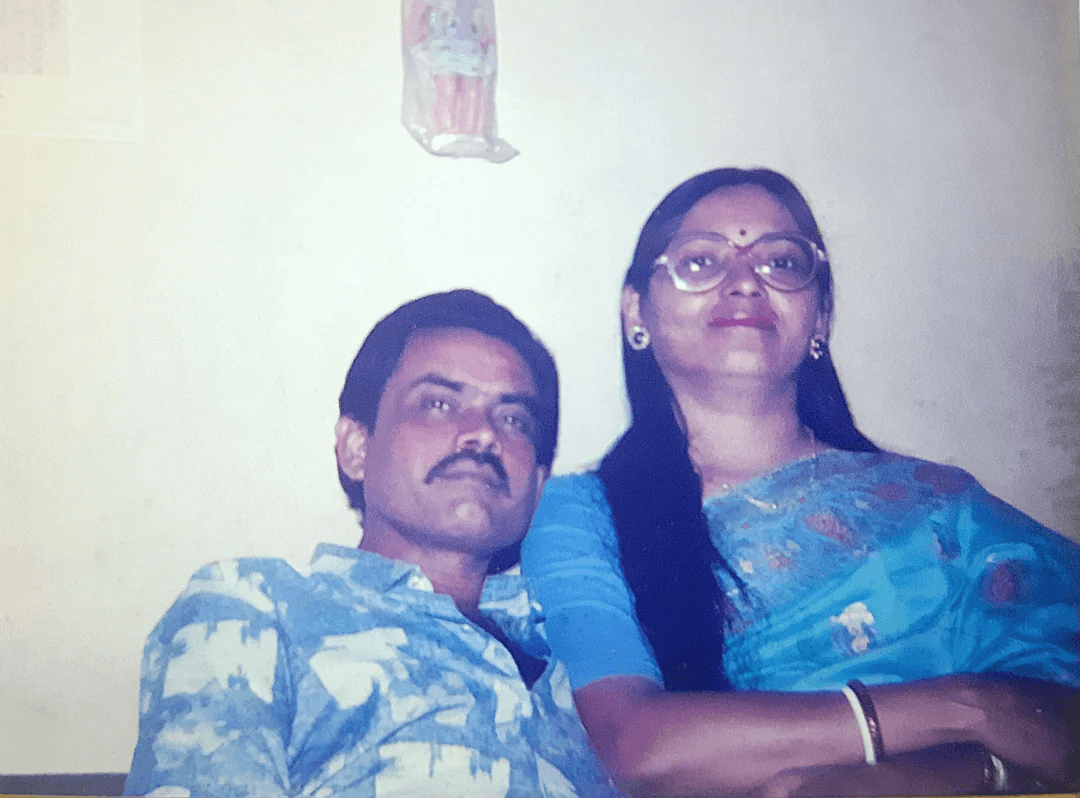

A glimpse of the kind of story your family could have, like Binod and Shraddha’s, collected through guided prompts and turned into a keepsake book.